In my travels and correspondence around the world, I find much confusion centered on the use of coconut husk litter, commonly known (after aging) as coco peat or mulch, in crop production. I was first made aware of the product as a potential additive to mineral soil or peat lite mixes in the early 1980’s. The thinking then was that it had too many issues to use as a straight mix but did have some interesting side results when used as a fraction in a potting mix, or as a soil amendment to improve soil structure.

It was first introduced to the Royal Botanical Society in 1862 and proved successful initially but dropped out of favor because of the inherent issues with coco peat. Now it has exploded onto the scene in all manner of use from fraction to complete; but what are we dealing with and why such a delay in its acceptance into the general market?

To start, the physical characteristics of coco is unique in that it changes it’s physical and chemical characteristics dramatically over time. Green or newly harvested mulch is actually the dust (and broken fibers) generated by removing the fibers from the husk of a coconut. This is unusable at this point. After several months of decomposition, it begins to take on some usable characteristics of holding moisture better, the release of Potassium and other salts slows to a reasonable level, and the structure remains intact. There is a fairly short period from this point that the coco peat is usable in container plant production.

Ideally, the coco peat has to go further to actually work with the plant correctly, but by then much of the structure is lost and the usable time in situ is severely shortened. While later stages of coco degradation are very acceptable as a soil amendment, it is not suitable for directly growing in. Structural problems are, however, a small part of the issue.

Coconut palms and the utilization of seawater

In addition, the availability of the nutrients present is affected on a changing scale along with continuing decomposition. Coconut Palms have the rare ability to utilize seawater solution as its source of water. Seawater has a high EC, or Electrical Conductivity, which is a measure of how concentrated the salt level is. Plant cells do not exist in this range but much lower. For water to move into the roots of a plant, it has to overcome the Osmotic Potential of the membranes the water molecules pass.

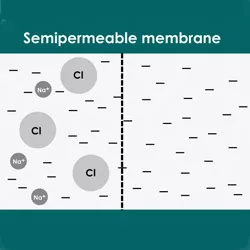

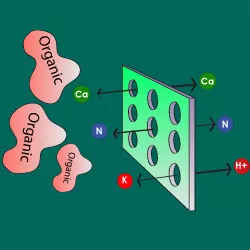

Water moves from an area of low EC to an area of higher EC in an attempt to balance out or achieve equilibrium; where a semi-permeable membrane isolates the two solutions, only certain elements or molecules can cross, typically a water molecule or smaller (selectively permeable), through the process of Osmosis. (Fig A-1)

Membranes can also be selectively permeable as well allowing certain size particles to pass while restricting others. (Fig A-2) In typical soils and container mixes, fertilized at recommended levels, the EC of the root zone moisture (which includes nutrients [salts]) is lower than the internal EC of the root cells, allowing water to move, or diffuse, across the barrier membranes. As root zone EC reaches EC levels of the plant, water movement slows and eventually halts.

Unfortunately, it does not stop here and is capable of moving the other way. In this manner, most ‘salt burn’ situations arise, but not all. To compensate and get the water in the seawater solution (it is a solution of water plus many and varied salts) to move into the plant, the palm concentrates salts in the areas between the cell walls known as interstitial spaces. This affectively shows an increase in the internal EC while allowing the actual cells to function normally.

Additionally, the process of harvesting the fibers also increase EC levels because the coconut husks are first soaked in seawater (the most abundant water supply close to where coconuts grow), which imparts its salts into all the pores of the coconut material. When decomposition occurs, these salts come out in very high amounts, especially Potassium, the most prevalent element found as an ion (salt).

Ions; usable nutrients

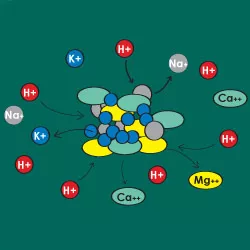

All usable nutrients become available to the plants internal processes as ions, or charged atoms or functional groups like nitrate. Ions affect each other, in fact, in the plants processes they are combined in controlled fashion. In a solution with other ions, and no controls, they still combine or associate with other ions of opposite charge. They also affect the availability of each other as similar charges. This is known as antagonisms, where one element in a large amount will decrease availability of another where it is in a smaller amount.

In this case as the concentration of Potassium increases, the availability of both Calcium and Magnesium decreases. It is more commonly known as locking out. When combined with the effects of pH and temperature, precipitation of these salts can occur. The effect works the other way when Calcium increases, potassium availability decreases. Additionally, Potassium has the ability to almost move at will throughout a plant, it is mostly unregulated; a characteristic all plants have adapted by harnessing these ions to do work as they move around.

This is all well and good, but how does that affect the use of coconut peat/ mulch with plants? As the coco decomposes, it ‘gives off’ salts that increase the EC of the medium which will result in burning and imbalances in Calcium/ Magnesium and Potassium balances or ratios; the ‘greener’ the coco, the worse the problem. About the time this ‘give off’ slows enough to really grow a crop in, the structure has the characteristics of muck peat and has to have amendments like perlite, sand, pebbles or other large particles added to it to give the medium air. Also, the state of decomposition is at its highest, so what is left will not last long, even being washed easily from the container. We know that if the level of salts AND the ratio of these salts could be controlled at an earlier stage, we would have the advantage of good physical structure and proper nutrient balance.

The benefits of coconut peat

Coconut peat has some wonderful physical properties that greatly benefit plant growth. To begin, it is renewable so no stripping of natures resources. It makes use of the final product left over from cultivating and harvesting the much prized nut. At the right point in decomposition, the coco peat can be used as a stand-alone medium with no need to add perlite or other persistent amendments.

The coco peat itself is fairly pH stable and buffers the pH well, in a very acceptable range for plant growth. While they are fairly solid and big early on, once the peat particles are treated and decomposed to a certain point, they are like sponges with micro-pores that hold water, away from the plant root but available to replenish the larger pores the plant root can access. This effectively limits excess water while holding water in a reserve status. These particles hold onto no ions, only what may fill and dry on the particles themselves, so as long as the medium is moist, nutrients are available.

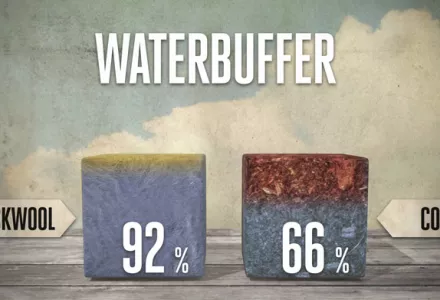

At the proper point of decomposition, the particles form the perfect combination of air-to-water spaces, because of the different fractions now present, which can actually mean more air space to water space with the micro-pores holding a reserve of water, giving a nice water buffer to the grower. There is no oil on its surface, unlike peat moss, so wetting the particle is never an issue. The key in all this is to decompose the particle to the perfect point to achieve this. The problem is still that the rate of salt given off remains high at this perfect point.

Well balanced growing

By controlling the decomposition process, adding the correct nutrient buffer to adjust the ratio, feeding the plants the correct ratio of nutrients to offset the coco ‘give off’ will produce the perfect growing conditions. When the medium is not taken into account, the results can be disastrous. Even when fed correctly, and the correct ‘buffer’ of nutrient ratio sets up, just one (1) watering with plain water will wreak the buffer sending the plant and medium into shock, rapidly escalating the potassium level.

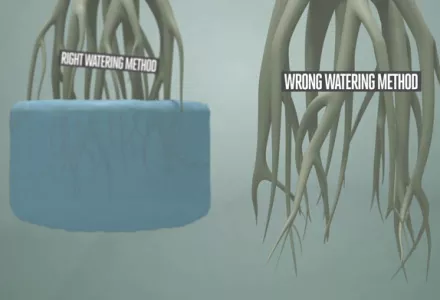

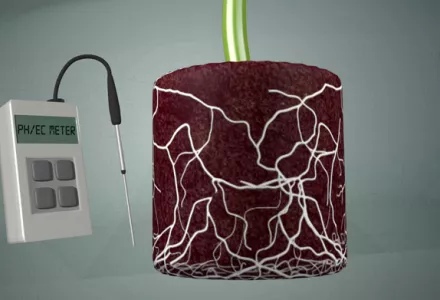

Consequently, plants that do not have enough of some ions like Calcium (there are several) from under feeding or washing out, will show deficiency in these and other elements while the Potassium builds up in the plant tissue ultimately to express as margin burning on the leaf surface, mostly at the tip. The first thing the inexperienced grower assumes is that they are feeding too high and have salt issues so they back up the feed concentration and leach the medium. This, of course, magnifies the problem and it gets worse. The key to proper coco growing is to use the right feed to balance the products the coco gives off, not just availability, but ratio of one to another mineral as well. (Fig B) It is equally important to water correctly.

Coco peat and moisture

Coco peat holds about 33 % more moisture then similar grades of peat based mediums if it is in good structure, but, because a great amount of this is tucked away in the micro-pores, the medium can look dry but still be plenty wet. (Fig C) The same rules apply here as soil or soilless mix, water when the container looses 50% of the maximum water it will hold against gravity (immediately after drainage of a newly watered container). Correctly this is done by weight and yes it does change with time, root mass, humidity, temperature and growers temperament (thumb on scale syndrome).

Coco and pH

Finally, the pH of the medium, when buffered and controlled, remains constant pretty much throughout its useful life. The medium sets its pH at between 5.2 and 6.2, perfect range, and will hold it there. Unlike peat based products that try to go back to a pH of 4.5 or less within 3 months of being planted.

By using the correct age of coco, with the right porosity, coco potting medium should be able to work through almost a year’s worth of cropping before needing to be changed. The pH stays correct and only the structure changes limiting its useful lifespan.

So, we see that by controlling the ageing process, using thercaorrnecteratio of nutrients, using the correct composients, and pre-buffering the coco peat, growers can anticipate getting the perfect medium, correctly balanced, correctly composed, with good porosity, a water buffer, and a lot less headaches then peat based soilless mix products. That is great for a start, but to complete a crop, it is critical that the correct nutrients be used as well. Consider coco as needing to be ‘fed’ along with the plants. Once the medium establishes a buffer, which it will do based on the nutrients it sees right or wrong; the grower can wipe this out by applying plain water to the medium. The medium hangs on to nothing and will readily flush away its nutrients; then the plant will suffer until the buffer is restored.

Always use fertilizer when you water coco that a plant is actively growing in, at least at about EC=0.6 mS/cm3. This will hold the balance or ratio of the nutrients to each other and insure that the plant gets exactly what it needs.

Coco is an ideal medium

Coco is an ideal medium. Plants thrive in coco when everything is right. (Fig D) There is one company that provides all the right components, CANNA. CANNA, always researching new pioneering ideas in the horticultural world, began exploring the coconut option when the peat was just giant piles of debris left over from the production of fibers. This debris was deposited around the landscape of producing countries in giant, rotting piles. Each year sees these piles grow higher. Initially these were the sources of coco peat for CANNA, but before bringing the product to market, they recognized the need for higher controls in order to receive the coveted RHP standard of Holland. They began controlling the product from harvest, through treatment, and into giant concrete bunkers to age to the exact level needed, then buffered, packaged and delivered to the market.

All this is done without steam sterilizing, which resulted in other beneficial consequences. By avoiding the steam sterilization to ensure RHP acceptance, CANNA also avoids chemical changes in the medium, nitrate conversions to nitrite forms (toxic to most life forms). The structure remains intact, the Potassium release remains a known variable, and the product is still delivered free from weeds, insects, disease and other soil borne problems.

One stop shop

Like all its product lines, CANNA believes in the complete package concept. Avoiding errors is essential. The Coco growing ‘system’, medium and nutrient line up, were engineered through years of in-house research and countless field tests to provide the correct growing solution, the exact composition and concentration of all the things required for using coco as a growing medium. (Fig E) CANNA COCO nutrients (and COGr) are designed to work with the exact properties of CANNA Buffered COCO (and COGr board). There is no better or easier way to begin and continue the Coco Growing Experience.